December’s a minefield. Most of the year you can watch movies or TV shows, and you more or less know what you’re in for. If you’re watching the latest Martin Scorsese movie, things will probably get heavy. If you’re watching a sitcom, the stakes will probably be low. Even now in the era of prestige TV and extremely niche indie films—when the writing is, I think, sharper than it’s ever been, and creators feel free to hop genres and assume their viewers’ intelligence—you can usually decide how much depth you want to deal with, and tailor your viewing accordingly.

But not in December—in December even the wackiest comedies have to stop the action long enough to meditate on capital-M Meaning, and the grittiest dramas make room for capital-M Miracles, in order to acknowledge the annual cultural fulcrum that is Christmas.

In all of my searching I have found only one film that ignores this tradition of meaning-making. That movie is The Nightmare Before Christmas.

The Nightmare Before Christmas is a fairly straightforward story: a living skeleton has a mid-life crisis and decides that, since orchestrating Halloween doesn’t make him happy the way it used to, he’s going to take Santa’s place on Christmas Eve. Over the course of 76 minutes, it draws inspiration from The Night Before Christmas, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, The Bride of Frankenstein, and, in a sideways way, It’s a Wonderful Life as Jack Skellington learns that his true happiness has been right in front of him the whole time.

But one thing the film does not do, which sets it apart from all of its referents, and as far as I can remember, from the entire Christmas canon, is give us any Meaning of Christmas.

All the specials The Nightmare Before Christmas riffs on provide Meanings like crazy: Charlie Brown gives us an explicitly Christian meaning, but builds on that by gently implying that offering love and acceptance to the broken—whether outcast boys or spindly trees—is part of the holiday; Rudolph bypasses religious references and posits that Christmas is a time for general openness, generosity, and found family; the Grinch steals all the “stuff” of the Whos’ Christmas, but comes to realize that “Christmas, perhaps, means a little bit more”—the special doesn’t go into what that “more” is, exactly, but the Whos singing and feasting together seems to be part of it.

Most specials, television shows, and movies, from It’s A Wonderful Life to VeggieTales to Stephen Colbert’s 2006 special The Greatest Gift of All! to the in-universe Bojack Horseman holiday episode, come to a head around an uncanny event: the confirmation of Santa’s existence, an angel/God saving someone, snow falling miraculously to save a vampire, or at the very least a vague idea of “Christmas spirit”—something extra-normal that brings people together. Hell, even National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation has the Griswolds gaze up into the stars while Clark gave a speech about the True Meaning of Christmas, and Home Alone peppers in a few scenes of Kevin McCallister going to church and bonding with an elderly man in between setting traps for the Wet Bandits. Even “dark” holiday films like Bad Santa and Krampus, or horror movies like Black Christmas, are self-consciously setting themselves against the usual holiday fare. The films depend on our understanding Christmas as a meaningful time so they can subvert our expectations.

But Nightmare’s Christmas stands apart: the film doesn’t want to bash you about the head with the idea that there has to be a Meaning.

The story begins in an extra-normal space and proceeds from there. Jack is a (seemingly-immortal) living skeleton who is the King of Halloweentown, which also democratically elects a mayor. Makes sense. Everyone in Halloweentown is supernatural: ghost dogs, vampires, werewolves, clowns with tear-away faces, etc. Halloweentown exists in relation to realms dedicated to other Western holidays: Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter, Valentine’s Day, and, bafflingly, St. Patrick’s Day. (I would kill for a sequel that takes us to the inebriated horrorshow of St. Patrick’s Day Land.) So we can guess, from what we’ve seen in Halloweentown, that the other holiday worlds are also full of immortal beings, including Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny. But having started from this place of mythology, where vampires and Santa and St. Patrick are all equally, indisputably real, the film goes on to focus on the stuff of the holidays. And it may be the only Christmas movie where the “Meaning” of Christmas isn’t ever found.

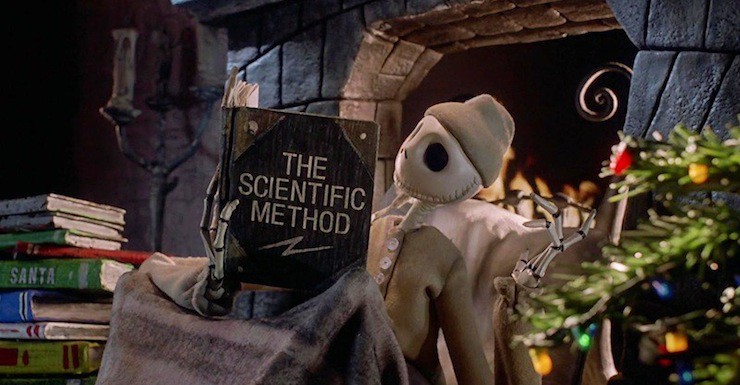

And what of Jack? It’s his existential crisis-turned-conversion experience that fuels the movie. He wants to understand the feeling of Christmas—”invisible but everywhere”. In order to do that he studies snowflakes, ornaments, candy canes, repeatedly asking “What does it mean?” and later sings:

Simple objects, nothing more

But something’s hidden through a door

Though I do not have the key

Something’s there I cannot see

and, a moment later:

I’ve read these Christmas books so many times

I know the stories and I know the rhymes

I know the Christmas carols all by heart

My skull’s so full, it’s tearing me apart

As often as I’ve read them, something’s wrong

So hard to put my bony finger on

—implying that Christmas is a feeling or spirit that he can’t access. Finally he declares that “just because I cannot see it, doesn’t mean I can’t believe it”—but believe what, exactly? Before he nails down what the elusive feeling is, he decides that the only way to get closer to it is to embody Santa. He’s like a Catholic convert deciding to skip CCD classes and instead become Pope.

As the film continues the embodiment of Christmas is more explicit. The song “Making Christmas” shows us that the rest of Halloweentown thinks that the holiday is a thing to be manufactured, literally, through the production of presents. And when Sally’s fog rolls in and the little boy says “There goes Christmas”, it seems that they all think “Christmas” is the act of going into the world with gifts and wreaking havoc.

And then of course we come to the most important part of the movie. When Jack gets shot down on Christmas Eve he is saved by a signifier, not the signified. Not a real angel, a Clarence or a Dudley or a Feist or a Dolly Parton, but a statue of an angel, stone-carved and silent.

Jack sings “Poor Jack”, and realizes he’s screwed up, and decides to give being The Pumpkin King another shot. This is also the film’s only reference to God (also rare for a Christmas movie to not have at least a light implication of divinity) which implies that God exists in the universe of the film, since Santa, the Easter Bunny, and Jack himself all do. But here again, what does it mean? As I mentioned, Jack is the undisputed, immortal ruler of not just Halloweentown, but Halloween as a concept, and yet when he wants us to know he’s serious about something he invokes a deity that is never otherwise mentioned. So why bring it up now, in a theological vacuum? The holidays represented in the forest between worlds are all Western, commercialized holidays that can be practiced as easily by secular people as by those who are religious. There isn’t a tree-portal for either of the Eids, or for Buddha’s birthday, the Feast of the Three Kings, or Yom Kippur. So when Jack uses the word “God” how are we supposed to take that?

I mean, I don’t know, I’m legitimately asking. This has been bothering me for years.

But to get back on track: none of this brings us to any conclusions about what constitutes Christmas in this story. According to the narrative beats in most Christmas specials, this should be the moment when Jack reckons with a larger Meaning of Christmas. But what he focuses on instead is that he messed the holiday up, and, crucially, that the way to “set things right” is to set Santa free to deliver presents.

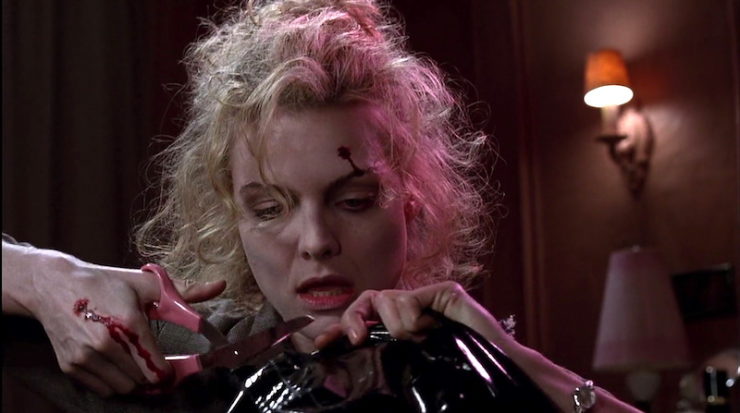

Which means Santa isn’t rescued by angels or elves or red-nosed reindeer—initially he’s saved by Sally, who does a rather disturbing riff on a striptease to distract Oogie Boogie. After she’s captured, too, it’s left to Jack to swoop in and set the two of them free. (My colleague Emmet Asher-Perrin insists, and I agree, that the subtext here is that Jack and Oogie had a thing, a serious THING, and at least some of the viciousness of the battle is fueled by that? It would certainly explain the tone.) The big final boss battle isn’t between Good and Evil, Santa isn’t powerful enough to save himself, there is no cosmological safety net—the stakes seem to be that if Jack fails, not only will he, Sally, and Santa die (whatever that means in this universe) but also that this will… end Christmas? All because Santa won’t exist to deliver presents.

But that whole existential abyss is moot, because Jack wins, straight up murders his enemy, and then anxiously asks Santa if he can fix everything. Santa, who has just been kidnapped, tortured, and just watched a bug monster die at the hands of a living skeleton, says “Of course I can fix it, I’m Santa Claus!” lays his finger alongside his nose, and flies away.

And…that’s it. There’s a montage of Santa doing a Christmas Eve speed run to replace all of Jack’s (fucking awesome) presents with more traditional ones. (Again, since only Christmas is represented, and Christmas’ entire purpose is receiving gifts from a Santa Claus who is objectively real in the universe of the film, any families who don’t celebrate Christmas are presumably screwed out of this windfall.) Santa even takes the time to swing by and give Halloweentown its first snowfall. But this isn’t miracle snow. This isn’t snow falling to save Angel the sad-sack vampire from sunlight, or a sudden cold snap to re-incorporate Frosty, or rain changing to snow to tell us that George Bailey is back in the right timeline. It’s just snow for snow’s sake. Jack and Santa don’t have a heart-to-heart about the essences of their respective holidays. The rest of the citizens of Halloweentown are openly relieved that Jack is back to normal. And the big culminating image isn’t anything to do with Christmas: it’s Jack and Sally kissing in the cemetery, which does not complete the narrative throughline of the movie. Their romance is a (lovely!) cul de sac.

The opening of the movie is that Jack feels empty, and that his life has lost meaning. He discovers Christmas, and makes learning Christmas his new purpose—but he never actually learns the Meaning of Christmas. “Jack’s Lament” and “What’s This?” are all about searching for something indefinable, and “Poor Jack”, the song he sings after he realizes he can’t be Santa Claus, muses on his failure to find it. And sure, he realizes that his job as the Pumpkin King is actually what he loves, but a verse before that he basically says he should give up and let himself die because he can’t understand Christmas.

So maybe the film does think the holiday has some intrinsic meaning, and acknowledges that the dispensation of presents isn’t it, exactly, but neither the hero nor the audience are ever given access to the “something hidden through the door.” Christmas rolls on, Jack’s friends and colleagues go back to normal, Dr. Finkelstein has a new bride, Sally begins a partnership with her crush. But Jack is never allowed into Christmas, whatever that means.

And that’s… OK? I think part of the beauty of The Nightmare Before Christmas, and part of why it’s become such a classic, lies in Jack’s ultimate failure. He tries really hard, but in the end he never quite gets it, the movie never holds his bony hand to explain it—and that’s fine. The movie also never sits us down to lecture us about the True Meaning of any of the holidays. It allows us space to celebrate however we want! Or to not celebrate at all, and instead bask in the beauty of killer stop-motion animation, free of the pressure to think about what any of these holidays mean to us. And isn’t that a beautiful relief from the whirlwind of emotion and expectation we fall into each December?

The Nightmare Before Christmas came out 27 years ago. Damn, I feel old, ugh.

I think the specialness of Christmas is all that truly matters in this one, and all they’re going for. Each person and thing has its place, and even when someone steps out of line (like Jack does, big time), he’s obviously forgiven by the offended party (Santa) in the end. No harm, no foul. Because it’s a bit of a fairytale world.

One could even deduce a bit more world-building and meaning from Patrick Stewart’s original opening.

It recently occurred to me that the “message’ of this movie might be to show the difference between “cultural appropriation” and “cultural appreciation.” Jack thinks that because he can’t “get” Christmas, that he has to remold it into something familiar that he can then act out, and by the end, comes to realize that he can just enjoy it for what it is even it it’s not part of his own zeitgeist.

Agree with #3, I think the point of the movie is that happy feelings and connection cant be manufactured or stolen, you either do or you dont and be grateful for what you have

I always came away from the film believing it was about all the things you mentioned; Jack feeling empty doing the same ol thing, discovers a new purpose trying to understand/take over xmas, failing, then realizing he was always right where he was meant to be all along. Which, to me, held enough meaning. Stay in your lane. Stick to your main purpose. And be really good at it. Grass isn’t always greener.

Like you, I also believed the love story and the smoochy smoochy ending to be just a cul de sac.

Interestingly, many other people I speak to see it entirely as a love story. With all the other stuff as the cul de sac. This interpretation always annoyed me for some reason. As it seems to discount all the other themes that, to me, make this story so great. Love stories are so cliche, after all…and this movie was anything but.

After reading your article, however, now I’m not so sure. As I never stopped to think about the Christmas meaning angle. Now I’m left wondering, if maybe these other folks were right all along?

If taken as a love story first and foremost, and Jack’s arc as the cul de sac, we may have found our meaning.

Something was missing for Jack throughout the whole film. He was going through the motions at work. Searching for superficial things to fulfill him. Then, this shiny thing called Christmas comes along and he thinks that must be the solution. Just recreate it. Take it over. And that must be all there is to it, right?

Wrong. His failed and hollow attempt at taking over Christmas, and misinterpreting its true meaning, finally gets him to realize what was truly missing this whole time. LOVE.

Without it, he was always taking for granted the greatness of what was staring him in the face all along. That is, being the greatest Pumpkin King you can be…and of course, Sally.

These things were always there. Just missing the Love behind it.

We all know, that it takes failure to finally succeed. With Jack failing at his first swing at Christmas, he finally gets it. It was more than just playing dress up and delivering gifts. The true meaning runs deeper. This whole time, Love was the main engine driving Christmas. Jack gets it now.

He puts a little Love in his heart and it changes everything. He is now ready to Love himself. And others.

And is rewarded by this epiphany with an unprecedented snow fall in Halloweentown. A gift from Santa Claus. Who after being kidnapped by Jack, and put through all the horrors he had to face because of him, still holds unconditional Love for the misguided Pumpkin King.

So yeah, maybe it was a Love Story after all.

it seems that they all think “Christmas” is the act of going into the world with gifts and wreaking havoc. Hey, that’s my true meaning of Christmas!

The meaning is that Christmas can be whatever you want, everyone celebrates different ways. The nightmarish toys were terrible for the human children, but perfect for the Halloweentown residents.

@5 I think you nailed it!

Jack feels that who he is isn’t special enough, so he tries to force being something else. But he isn’t being true to himself, and ends up learning to be happy with himself as he is. A good lesson for us all.

If you enjoy the music, I highly recommend Voiceplay’s channel on YouTube, particularly their version of the “Oogie Boogie Song.”

Finding the meaning, small “m,” isn’t figuring out what the outside meaning of Christmas or Halloween is to everyone but figuring out what it means inside of you. Plus, love.

If they do the desired sequel, I think it’d be the nightmare after St. Patrick’s Day (waking up hungover with a puddle of your own sick in your novelty plastic leprechaun hat).

Jack doesn’t learn the true meaning of Christmas, but the experience renews his faith in Hallowe’en. I think the movie is more about the true meaning of Hallowe’en, which is scaring the hell out of everyone….

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

I wish I had something better to add, but in a way I’ve seen it to be a bit of a message about staying in your lane, appropriation, etc. It’s great that Jack is inspired by Christmas (and maybe even gets some new ideas for Halloween) but not so great that he tries to remake Christmas in his own image. Each holiday has its place and specialness and room for expression. Although I can also understand the desire for something new. Maybe they can do some cross holiday internships here and there ;)

But I also kind of like the idea that it just points to the ineffable mystery of Christmas; it’s not something that can be calculated, manufactured or is just about the presents and the costume and the trappings.

As an aside, it never occurred to me that all the holiday doors are not just kind of typical secularized holidays, but also holidays that have a personification (which may or may not be in line with the figure who inspired it). Which begs the question, what goes on behind the doors of Valentine’s Day world lol.

I agree with comment#5 and enjoy that perspective with a plus. Not being christian and yet celebrating Christmas and Easter in a secular way since childhood, I had to look deeper to see what the holidaying is really about. One of the first things I found while looking into origins and meanings of these holidays, I stumbled upon a spiritual value. Not anything connected to deities or religions but a human need for each other. Our human needs can be explained through chemistry like neurotransmitters and hormones. So it turns out that Oxytocin has the properties we need to feel good and right with the world. We get Oxytocin boosts from doing a variety of things. So Jack has a longing. He sees joy and gladness in this Christmas Town. When we are creative and do things for others we get an Oxytocin boost. With winter nights and coldness tugging at our bones we congregate which brings up our spirits. It is well known that December has a solstice which has been long celebrated for it’s significance being the end of the earth cycle of darkening, like the end of our year represented by an old man. Then we understand the sun has a rebirth as the days will now start to become longer. This re birthing of a new year is represented with a baby. We have so many symbols generated around this celestial event because humans are so creative. So as Jack searches for something to fulfill him, he is doing what many of us do in our lives and what Danny Elfman himself said how Jack was him during the making of this movie with his career and all. Incidentally and equally important to this story is that the whole story was a collaboration of many including Danny Elfman’s then girlfriend, who he was living with temporarily during construction on his own place. She was there as he was struggling to put this concept into music, song and storyline. His girlfriend Caroline happened to be a script writer and was chosen to sew the bits up into a tidy package and included herself in the story. If you have ever seen her, you know that she is the origin of Sally. Sally looks like she is fashioned after Caroline.

This Nightmare before Christmas is such a masterpiece because of all the passion from so many expressive artists went into this entire story. And the meaning is that life has joy when we celebrate with each other and hold on to the love.

. I remember the vhs of the movie and once i noticed the case was black and not white i knew it would be my favorite. “Different” did it for me but once i watched the movie i had to sing every verse and know every line. Now I’m 34 years old and still remember everything and i now know there’s more to the movie then awesome lyrics and animation.